di Timoteo Carbone

[Sonic Acts è un importante festival di musica sperimentale e arti multimediali che si svolge ogni anno ad Amsterdam dal 1994. Timoteo Carbone, compositore e sound artist di stanza a L’Aia, ha seguito per musicaelettronica.it l’edizione di quest’anno (21-23 febbraio 2020) e ha intervistato due artisti ospiti del festival. Qui di seguito, la seconda parte del suo report. Per la prima parte cliccare qui]

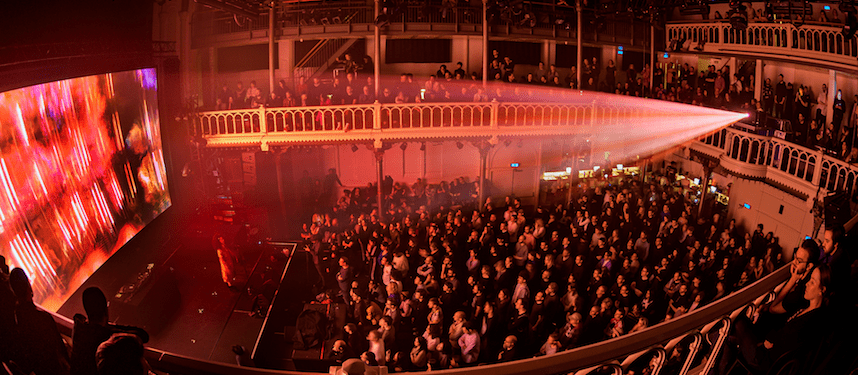

Incontro Roly Porter il giorno dopo il debutto della sua nuova performance multimediale Kistvaen. Il lavoro si crea da un lungo processo di ricerca intorno ai Kistvaen del Dartmoor, lasciti funerari di pietra del tardo neolitico scoperti nel Galles. La performance è frutto di una collaborazione con Marcel Weber, in arte MFO, e della cantante e ricercatrice Mary-Anne Roberts. Kistvaen è stata un’esperienza immersiva che ha fatto uso di suoni surround, video art e della performance dal vivo di Roly Porter e Mary-Anne Roberts.

Una volta seduti al caffè la mia prima domanda è sulla collaborazione con Mary-Anne Roberts.

Roly Porter: Well, Mary Anne Roberts is an amazing singer, she’s Trinidadian and has lived in Wales for 15 years or something like that, maybe longer. She’s part of the project called Bragod, which is a duo with another musician, Robert Evans. Bragod researches and performs historical informed musical techniques and pieces from medieval Welsh early music. So, I first heard the music many, many years ago and her voice is so distinctive that I was always obsessed with the idea of working together. When I began developing this project, which is based around an imaginary Neolithic burial ritual, I wanted to have a vocal style in it that didn’t contain recognizable language or kind of melodic conventional melodic styles, but was based on my imaginary perceived sound of this ritualize burial ceremony in Neolithic times. So it’s a combination of a kind of ceremonial call and an emotional wailing. She’s just the ideal person for this project: her range, dynamic range and a pitch range is so wide and because she speaks often sings in welsh medieval worship dialect. She has a lot of vocal sounds that are more connected to guttural sounds, I guess those sounds that they have here in the Dutch language or in Celtic languages. A lot of sounds that we’ve lost in the English language. They really work with that kind of non-linguistic, non-language emotional call.

- La voce di Mary-Anne mi ha ricordato a tratti dei canti diafoni tibetani. La sua voce ha veramente dei colori incredibili. Come hai impostato la collaborazione? Hai scritto una partitura?

Actually, before I met her, I spent some time developing the idea with another singer in Bristol, a male singer and an archivist. He is interested in more Slavic folklore traditions and I did spend a lot of time trying to create pictorial scores, and it was moderately successful. While, with Mary Ann and her ability to improvise, the way of that she embraced so strongly the concept behind the project, actually it wasn’t necessary to make any score at all. After 20 years of sound design I still haven’t created anything that is as incredible as the human voice. That’s the most frustrating and amazing thing about the human voice. When I first meet Mary Ann, just sitting in a tiny room and hearing her singing for the first time… I just burst into tears.

- Tanti anni fa vidi nella televisione nazionale svedese un documentario sulla liuteria tedesca. Un famoso costruttore di violini, alla fine della trasmissione, affermava che, nonostante tutti gli anni di esperienza, i suoi violini non riuscivano a superare la bellezza della voce umana. Una perfezione che, secondo il liutaio, non poteva essere superata perché creata da Dio.

Although I suppose you would also argue that God created the violin through him though…

- Come dice un mio caro amico di Den Haag: Dio non esiste, quindi non ti preoccupare di queste cose! Nell’assistere alla performance ho trovato che esiste una forte connessione col concetto del lamento e del rito funerario…

The specific idea in this project is that evolutionarily in the Neolithic period humans were in a very similar stage physically and emotionally to what we are today, with technological differences. We think of that period as prehistory but, emotionally, people would have been the same to some extent.

- In che senso?

In the sense that the kind of social evolution was more or less where we are today. There has been great advances, for which we have technological and cultural differences now. They were living in an entirely different landscape, without any other kind of structures or technology that we have today, but they would have experienced a lot of the emotionality of death in the same way we do today.

Archeological studies of that time shows that many rituals were emerging and developing. Social rituals and agricultural processes. Many things that are coming to the an end now, in this period that we’re now transitioning. Out of a sort of rural period in a more technology-based time. So I wanted to explore with the voice a kind of completely instinctive emotionality, that’s the main reason I don’t know the language I use in the performance, it’s supposed to be a sort of timeless emotionality around death and around the ritual of burial.

I’m obsessed with Western religious music and Christian music of the past: the relationship with death within these rituals, which are still very much part of christianity today, feels very unnatural to me and very incorrect.

- Tenendo conto di quanto detto, trovo ci sia una differenza di come gli uomini, sia come individui e sia come comunità, toccano il tema della morte naturale rispetto a come, adesso, tocchiamo il tema della morte ecologica del mondo. Come si è sviluppato il tema dell’ecologia nel tuo lavoro?

When I was younger I had an obsession with mortality and then, as I grew older, I came to terms with that. Having children, you begin to realize that actually the natural cycle is in many ways a beautiful thing. The environmental aspect and indication in the show came from Marcel Weber. It was his idea really to bookend these two parts of History, the late past and modernity. In the piece we move from day setting into night. We also jump forward in time to images of forests to images of hydroponic farming, which were shot in Poland and the Netherlands.

Basically the end of this period of rural technology and development. The problem is a lot of those images draws parallels with artworks like Koyaanisqatsi, obvious parallels of juxtaposing nature and technology and that’s not really what we’re trying to say necessarily. We are not saying that the images of the beginning of forests are innately good and these images of modernity at the end are bad. It’s literally just this transition from night to day and through time. It is not judgmental, it’s not an environmental piece of activism or commentary.

- Come si è sviluppata la parte visiva della performance?

I mean, obviously Marcel (Marcel Weber, aka MFO) would be better placed to answer these questions. There’s a sort of structural issue with having an audience, the performer and a screen in a kind of conventional DJ format. Firstly, if you spent two years making a film you don’t want two people stand in front of the screen. That’s purely from an aesthetic point of view. The film it’s not a backdrop to performance, the film is a cinematic experience and it was designed to be watched like that. So, what we wanted is the physical dynamics of the auditorium. There are three basic chapters to the piece and one of them is performative, which is where Mary Ann is the sole focus. So, the piece begins with just a singer on stage and no video. Then we enter a cinematic phase where there’s no singers no performers, and it’s purely Cinema. Finally, we have the attempt to break up the forward-looking direction. So, Marianne sings from either from within the crowd or from the balcony as it was the case of last night. The project was led by a decision to get away from the idea of audiovisual works being a kind of accompaniment to a conventional electronic music show, the project aims to be more a sort of designed cinema.

Tutte le immagini © Pieter Kers

Lascia una risposta